“No changes were made to your original file”

Today’s blog post makes a few observations about the way file formats behave. To be more specific, we’re talking about MS Office documents and what happens to them in MS SharePoint.

In my superficial way, I have noticed that when a document gets uploaded to SharePoint we can now look at it through a web browser. This is because SharePoint is predicated on the idea that we can all work in the cloud instead of being tied down to a local server. The browser view we are offered is not unlike Windows Explorer. In this view, we can see a folder structure, a file name, and also columns indicating dates (the Modified column), the Owner Name (Modified By) and Size (File Size).

I could see in this view that when a document gets uploaded, the date displayed is the date when it was added to SharePoint. This made me wonder what happened to the original Date Of Creation, something we worry about if we’re archivists or records managers. Further, I wondered if other metadata was being affected by this drag-and-drop action.

Tests

I did some tests using the Apache Tika utility, which is capable of exposing Properties in many file formats. In the case of Office documents, these properties can be a rich mix of dates, text strings, and technical metadata. I’m naively assuming these things are inscribed in the document in some way, by a combination of the application (e.g. MS Word) and the Windows file system, e.g. NFTS.

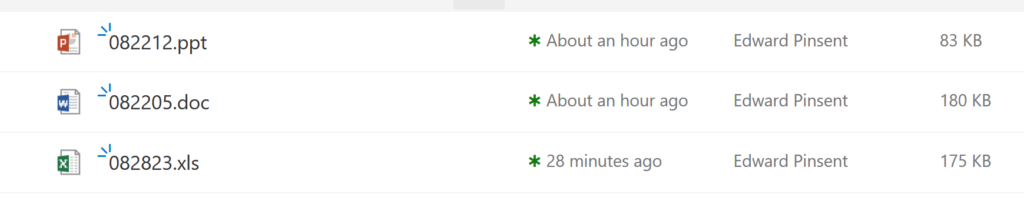

My method was to start with a small test bed of Office documents (one .doc, one .xls, and one .ppt). I got these from the OPF format corpus. I wanted to carry out a simple before-and-after comparison. First I profiled all the documents before upload, and pasted all the metadata into my table.

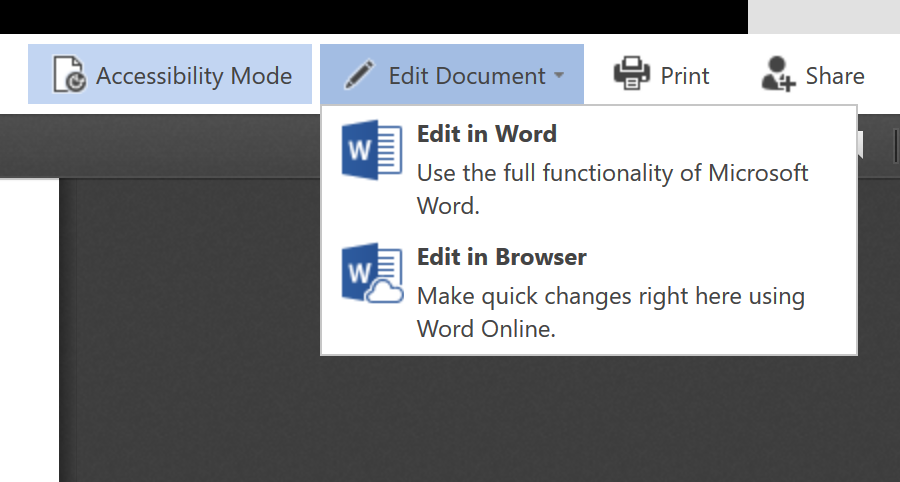

Then I tried three operations using SharePoint: (1) Drag and drop (2) Edit in the Browser (3) Edit in Word. The first one is simply moving (copying) the document from Windows Explorer into the SharePoint environment. The editing operations refer to the two options available: “make quick changes in the Browser”, or launch the application for more functionality. (2) suggests there is a web-based version of Word, Excel and PowerPoint which doesn’t quite have all the functions you’d expect, but still enables a user to carry out some limited edits.

After each action, there was a change to the test object. I downloaded the changed object in each case, and ran Apache Tika to see what the profiles looked like. I then pasted all the results into my table so I could make comparisons.

Click to download comparative tables

What changed?

There’s a number of changes which you can see if you download my tables. Look at comparativetable.xlsx. The most obvious and profound change is to the dates, especially the date of creation. This property remains unchanged if we just drag and drop; but when we start editing, either in browser or in application, the date of creation appears to change to the date when editing was carried out. The PowerPoint file kept its date of creation, but the other two didn’t; so now the only evidence we have of original dates is in the “Date Printed” property.

The second profound change is to the file size. In each case, this changed quite noticeably; even the act of dragging and dropping introduced a change to file size. Given the fact that the checksum is also new, it looks as though SharePoint is creating a new digital object in some way, and “injecting” it with something (I have no idea what) that makes it larger.

We’ve also tended to lose properties like Last-Author, which can get overwritten in SharePoint. In one exceptional case, there’s also a puzzling report on the page count of my Word Document, which mysteriously changes from 1 page to 29 pages.

What about newer documents?

So far so good. However, this experiment has been applied to “old” Microsoft Documents, by which I mean documents authored before the introduction of the Office Open XML standard. I thought I had better try out the same experiments with some more recent documents, and so selected a testbed of one .docx file, one pptx file, and one .xlsx file. The same before and after actions as above were carried out. Results are available in my second table, comparativetable_2.xlsx.

This time the changes were nowhere near as profound. In each case, the Date of Creation is intact, a result likely to reassure obsessive archivists like myself. There are still some minor losses but most of the elements highlighted in red are as expected (i.e. they reflect that fact that editing took place). However, SharePoint evidently still continues to “inject” something to make the files change size.

What’s going on?

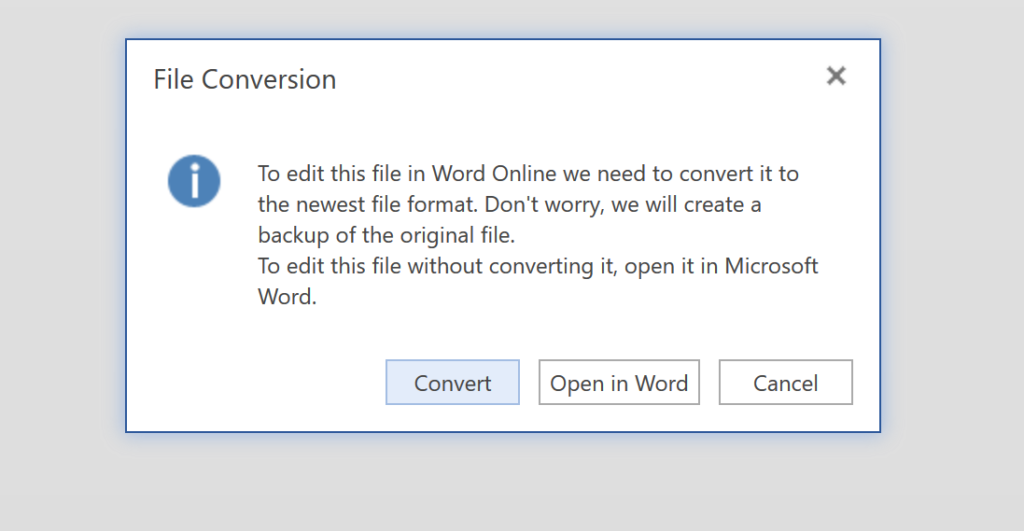

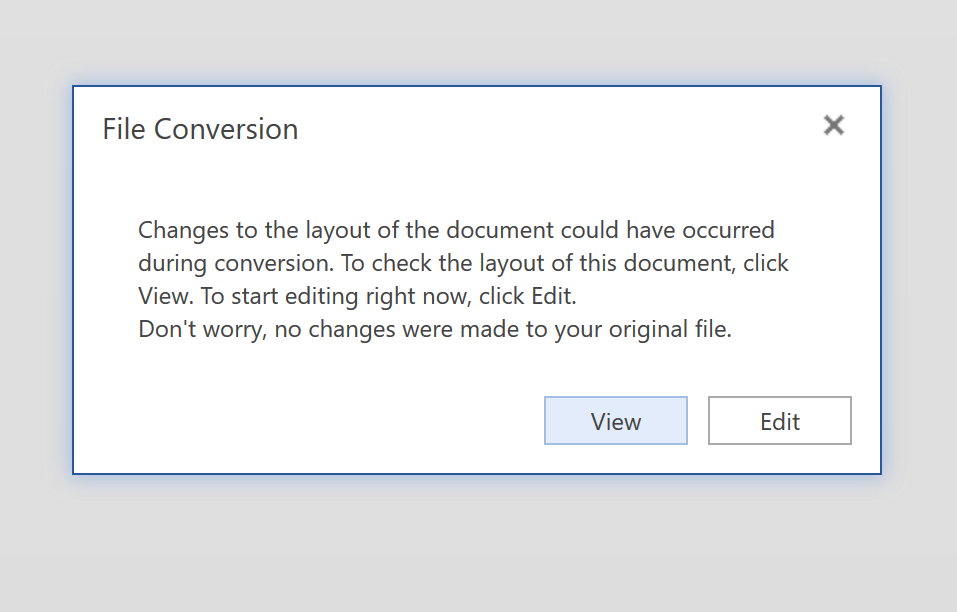

One thing that might be happening here is not limited to SharePoint, but reflects Microsoft’s commitment to forward compatibility. When you launch an old MS Document in a more recent version of the application, it offers to perform file conversion for you. The user receives notification messages that this is happening. Matter of fact we received such notifications in the course of this experiment, such as these:

One result of this is that SharePoint now helpfully stores two iterations of your file for you. One of them is the “original”, the other is the “conversion”. However, the extent of reporting on changes is restricted to a rather vague generic message about “changes to the layout”. Well, if my tests indicate anything, it’s more than just a layout change.

Does any of this matter?

From a digital preservation point of view, I would say yes it does. I don’t think any of us would be too happy about a process that seems to over-write the date of creation of a resource; and more to the point doesn’t really tell us that the change is happening.

I don’t think I need stress the importance of dates for record-keeping, and other embedded properties may also add value. Indeed, one approach to digital preservation as it applies to file formats is to carry out extensive profiling of ingested files, extract and copy the metadata, and store it within the Archival Information Package. If we’re even more clever, we can parse the properties into separate fields and manage them in a preservation database.

I’m aware that the value of doing this is disputed, and that we’re continuing to have discussions and conversations about “significant properties” in our community. But if any of my observations are correct, it seems that SharePoint is performing a species of migration on our content (they call it “conversion”), and introducing changes without really telling us the extent of these changes.

The lesson, if indeed there is one, might be that “old” Office documents need some care and attention before upload to SharePoint, if these properties are important to you and your users.

Additional thoughts

If we find ourselves moving content into SharePoint, do we have to do it by a drag and drop action? To put it another way, are there other ways of moving files so we can protect these properties? Probably. One possibility is the TeraCopy tool, and another possibility is file compression.

TeraCopy is a Windows tool which offers a more sophisticated form of drag-and-drop. It evidently integrates well with Windows Explorer, although the vendors don’t claim that it works with SharePoint. While I do have the free version, I haven’t experimented with it as part of this test.

TeraCopy includes checksum verification as part of its capabilities, which is why it’s bound to appeal to digital archivists. Additionally, it claims to do something to keep date properties intact:

As to file compression, this would involve zipping up the target files into a single compressed object (e.g. .zip or .7z) and moving this into SharePoint. In some other unrelated experiments, I have found this does indeed protect the dates and other properties from any unwarranted change. However, it’s arguably pretty pointless to put a zipped object into SharePoint, as this will probably obviate against the faceted views and collaborative aspects that the platform offers.