Counter-intuitive as it may seem, this blog post will try and advance the idea that embarking on a project to digitise your paper collections isn’t always a great idea. This isn’t to say you should abandon the idea completely, but we would encourage you to think it through. You could read this post as a sort of cautionary tale.

The Harvard report Selecting Research Collections for Digitization proposes a number of very sound reasons for why an HFE Institution should pause before it commits resource to any large and complex digitisation project. They provide the reader with a series of questions that will help a good project planner steer a way through the decision process.

Among the reasons identified by these experts, I will single out two of my favourite themes:

Is anyone even interested?

Look at the material you’re intending to digitise. Does it have any value? Do you think readers, users, researchers and customers are going to be interested in it? Even if they are interested, why does it improve the situation for them to access it in digital form? Will usage of the material increase? If you increase access to thousands more people around the world who look at the material through your online catalogue, is that a genuine improvement? Why?

The answers to these questions may seem to be obvious to you, but this line of thinking also can expose some of our assumptions and pre-conceived ideas about our relationship with our audience, and the real value of serving content digitally.

We might assume a collection is going to be popular when it isn’t. We might assume that simply scanning a book and putting images of the pages online is all we need to do. Have we even asked the readers what they would like?

Can you go on supporting it?

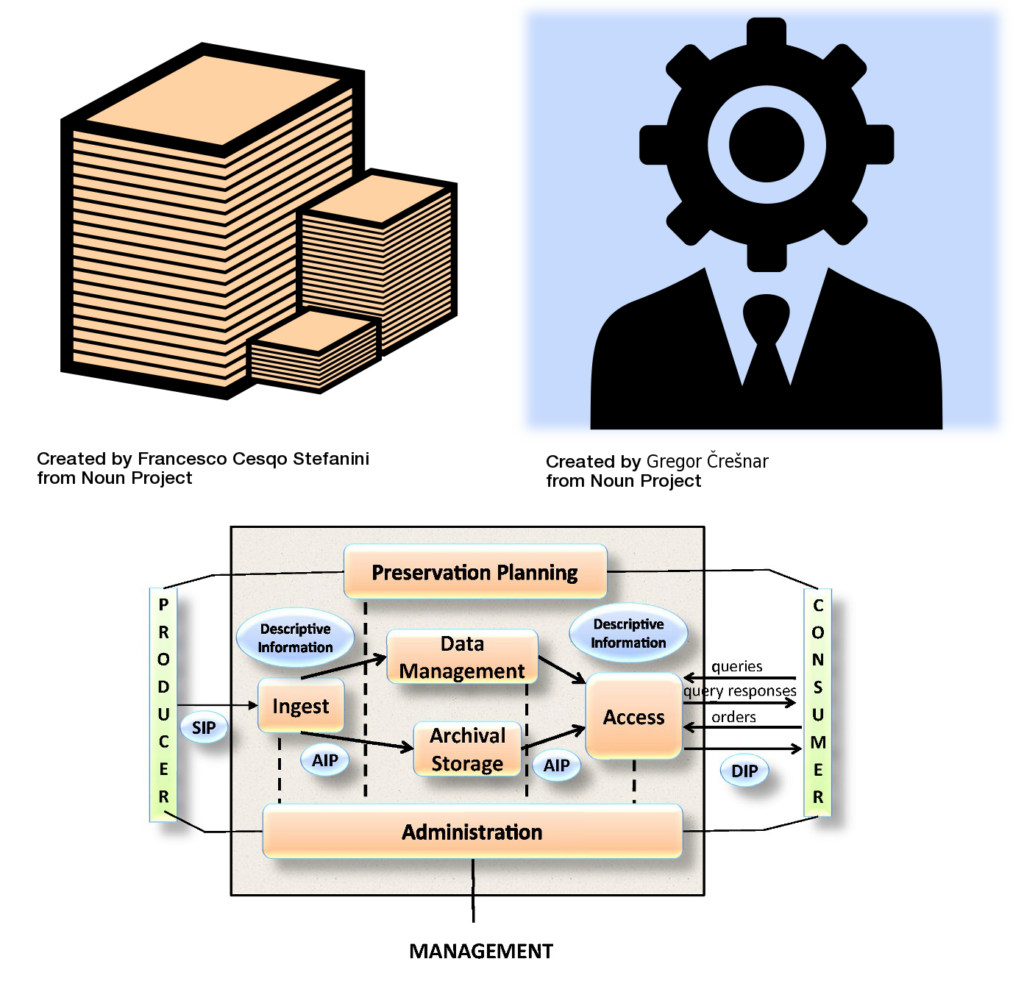

This is about the very real problem of ongoing costs. We may assume that once all the scans are produced, the project budget can be closed. In fact, it continues to cost you money to store, support, manage and steward your digitised collections; and that’s leaving aside the cost of long-term preservation, should you realise there’s permanent value in the digital material you have created. In short, it may cost more than you think.

My former colleague Patricia Sleeman did a survey of a number of HFE Institutions in 2009 who had received JISC funding to carry out digitisation projects over the previous decade. She found:

“Four principal themes surfaced through analysis of the preservation plans of the digitisation projects that relate the maturity of institution to the likely success of their digitisation efforts. These are the need for preservation policies; collection management procedures; robust preservation infrastructures; and sustainability. In short, institutions or consortia which have clarity in these four areas considerably reduce the risks associated with long term access to digitized collections.”

Both of these reports may have been aimed primarily at HFE audiences in a research context, but I think the lessons apply to any organisations, including those in the commercial sector who intend to digitise content.

You’re considering spending a lot of money on digitising this collection, and potentially committing the resources of people, technology, and time. If you proceed with the project on overly-optimistic assumptions, it can lead to difficulties in the future.

However, don’t let this discourage you…

When you’ve decided to say “yes”

The benefits of doing digitisation have probably occurred to you already (saves wear and tear on originals, disseminates more content to a wider audience, benefits the organisation, may help with income generation…). I also like to encourage project managers to rethink, if possible, what the collection’s potential is for engaging with its intended audience. Are we happy to continue the traditional model of the searcher visiting the searchroom and looking at a box of photographs with captions, only doing it in a “digital” manner? Wouldn’t we like to use web tools like page-turners and zoom devices to enhance and improve on the experience in some way?

The great thing is that if you’ve done scanning according to best practices, you can repurpose your resources (as Access Copies) in a myriad of ways, making the most of access technologies. You’re now opening the doors for a potential dialogue with your user community, responding to changes in user needs and repurposing the way you serve your content. All your hard work will have paid off.