In the previous post I made some observations about metadata in Office Documents in the SharePoint environment. In this brief follow-up post, I will mention what happens to PDF/A files in SharePoint. This is prompted by a comment received from Özhan Saglik. As part of this, I was also moved to try an experiment with Read-Only documents.

Well, the punchline to the first one is simple – PDF/A files don’t change at all in SharePoint. At least, that’s what I found with my limited testbed. This result need not surprise us, if we consider some basic facts:

- PDF/A files are designed to “open as read only”. This is part of the standard, so they can’t be (carelessly) modified by anything. Matter of fact you should get a message at the top of the document when you open it, informing you that this is the case.

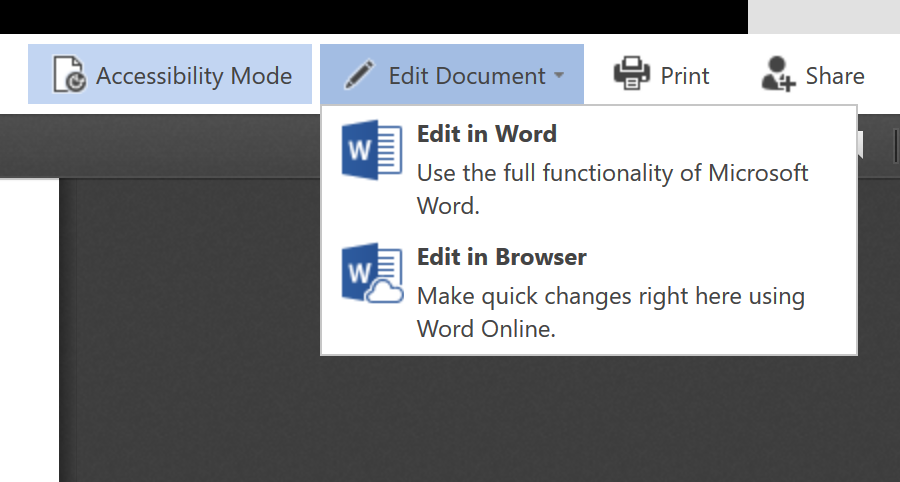

- SharePoint was designed to work with Microsoft products, not Adobe products. To be precise, the main purpose of working in SharePoint is the sharing and editing capability; the developers have not expended any effort in adding an editor or other app for a file format which they don’t support. On the other hand, you can upload a PDF to SharePoint and let others see it.

- There is no possibility of editing PDF/A (or even plain PDFs) within the SharePoint environment. See previous remark.

The above observations are endorsed by MS employees, for instance in this forum thread.

PDF/A experiments

For the record, for this experiment I used five files which are conformant to the PDF/A 1-a flavour. I can say this with a small degree of certainty because (a) this information is reported in their metadata and (b) they passed the VeraPDF test for conformance with the standard. As with my previous experiment, I did a before-and-after profiling of their properties using Apache Tika.

I was able to upload the PDF/A files into Sharepoint, and download them; that’s as far as it goes, since (as noted) no editing of a PDF within SharePoint is possible. All the metadata remained completely intact, and the upload-download process did not change anything. Results can be seen in comparative_table_3.xlsx.

Download comparative tables as a zip file (27.9 KB)

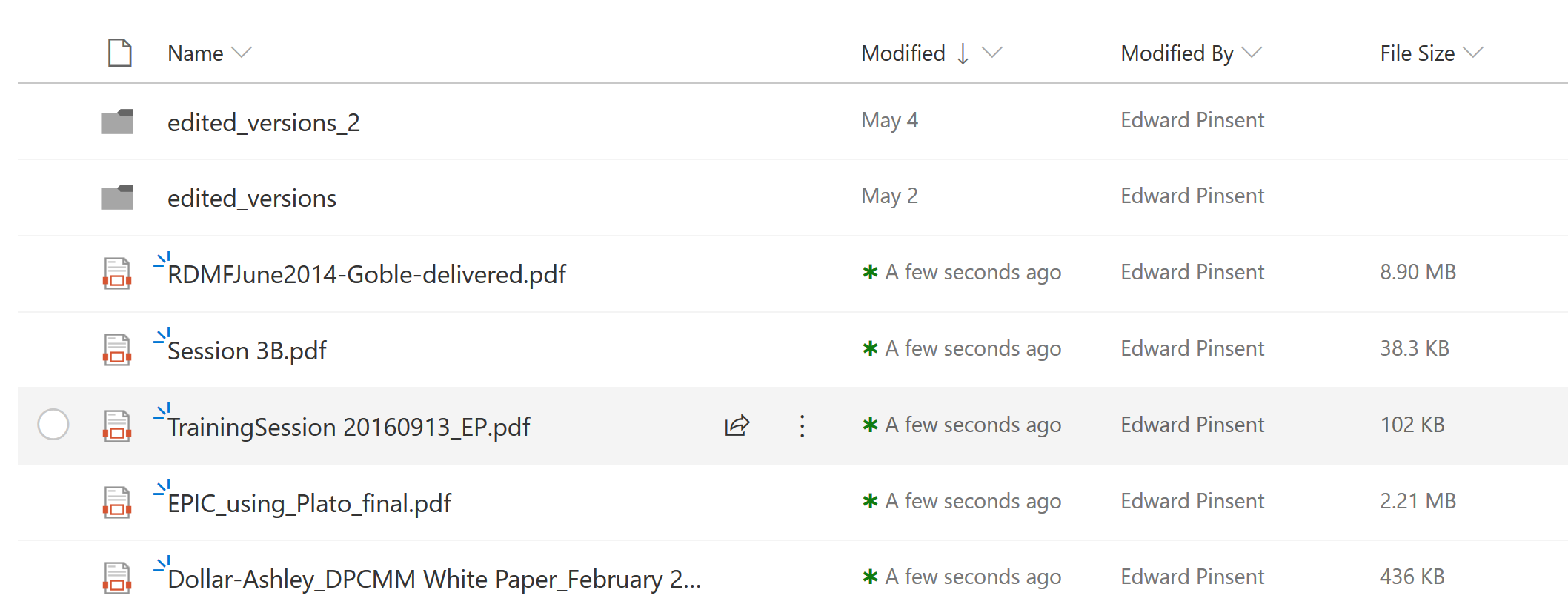

However, one aspect still intrigues me. It’s a property – or something – which is reporting on a date and time. It displays as “Modified” in SharePoint, and also displays as ‘Date Modified’ in Windows Explorer. I am assuming, perhaps wrongly, that both of these are the same thing. If we look at this screenshot, it shows my PDF/A files after I’d dragged them in:

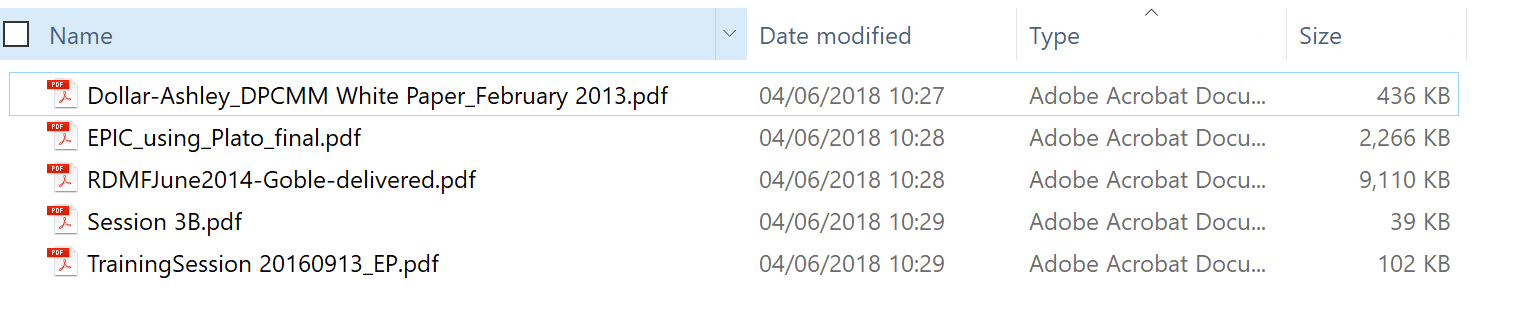

And after I’d downloaded them back onto my Desktop, Windows Explorer likewise reported today’s date:

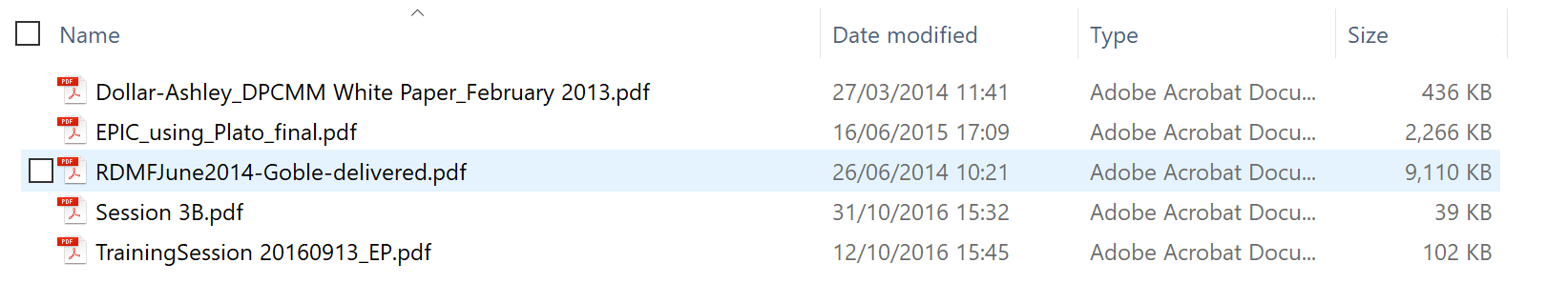

These dates in no way match the modified dates of the original PDFs as reported in Windows:

What’s also interesting is that I can’t find this “Date modified” value anywhere in the Apache Tika report.

I’m assuming that, in Windows Explorer at least, this is a timestamp, or a file time value which gets written by the NFTS system. These values change in response to certain events, such as copying or drag-and-dropping. This page seems to describe what I think might be happening.

Maybe Read-Only is the key?

I was about to scribble something along the lines of “PDF/A is a robust format – and here’s why!” Perhaps then setting myself the impossible job of understanding (and explaining) how the PDF/A encoding meets some of our expectations for long-term preservation by the complex set of conditions that obtain within the standard. But what if it’s much simpler than that? Perhaps a PDF/A file is impervious to SharePoint changes for one simple reason – it’s Read-Only.

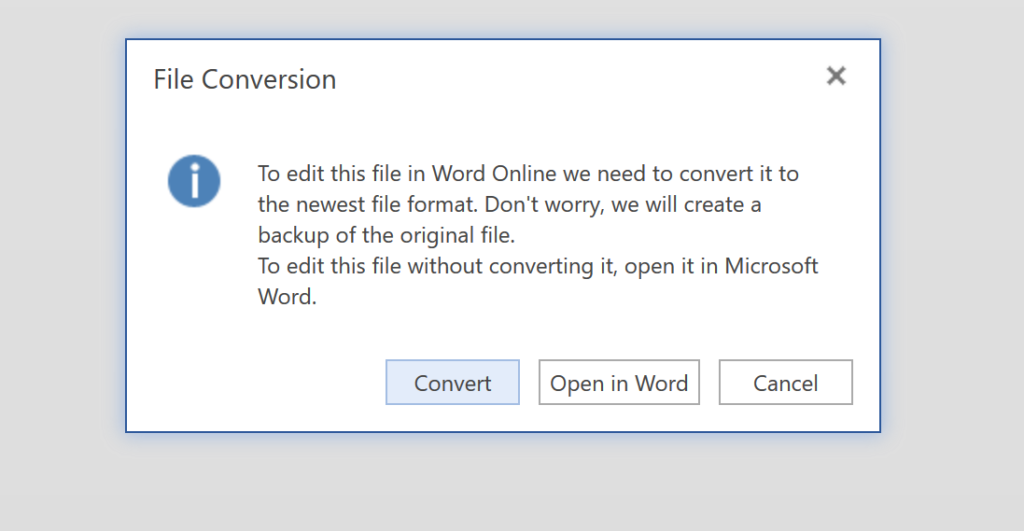

If that’s true, I wondered, then would MS Office documents behave nicely if I set their Properties to Read Only before uploading them into SharePoint, where the expected metadata changes would take place?

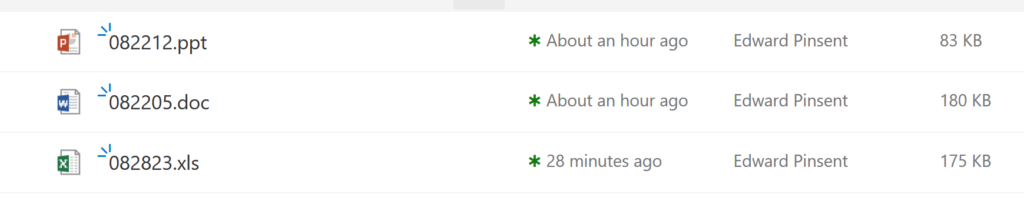

I decided to revisit my MS Office Documents testbed from the previous experiment and try this out. The results can be seen in comparative_table_4.xlsx. and were extremely encouraging.

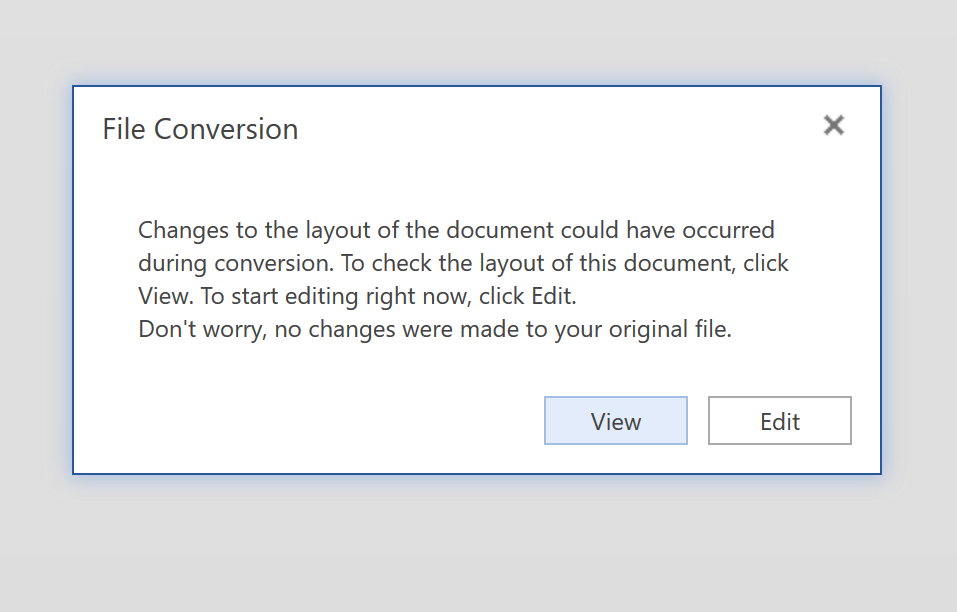

For the “old style” Office documents, the only thing that has changed between upload and download is the checksum. From this evidence, perhaps we might conclude that SharePoint has simply generated a “new” digital object in some way – which is pretty much the expected behaviour, is it not?

In the case of the three Office Open XML files, SharePoint added a new Custom Field that wasn’t there before. The Content Length also changed.

However, unlike what happened in my previous experiments, all the properties and metadata remain the same, including that all-important date of creation.

Lessons learned

- Documents authored to be conformant to the PDF/A standard seem to be impervious to change in SharePoint. This may mean the format is a good thing, from that point of view.

- Office Documents, if set to Read Only before upload to SharePoint, are much better protected from SharePoint change than those that are not. Of course, if you start to edit the document in SharePoint it’s another matter completely. But this way we stand a chance at least of uploading an authentic “original” document with metadata and properties intact, which could be used as a ground-zero point of comparison for any subsequent changes that are made.

- Ticking the Read Only box is a simple expedient which can be achieved without even opening the document (simply right-click on the object in Windows Explorer). A purist might argue that doing so constitutes making a change to the file which violates archival principles; but does it? Maybe we’re only ticking a box in properties which has no profound effect on the content. Maybe the added protection it affords us is a trade-off that is worth making.

These are not especially ground-breaking revelations, but they may help an archivist or records manager who is facing a SharePoint rollout, and provide some clues for a practical workaround which may help to mitigate this metadata loss.