I was very interested to hear John Sheridan, Head of Digital at The National Archives, present on this theme. He is growing new ways of thinking about archival care in relation to digital preservation. As per my previous post, when these phrases occur in the same sentence then you have my attention. He has blogged about the subject this year (for the Digital Preservation Coalition), but clearly the subject is becoming deeper all the time. Below, I reflect on three of the many points that he makes concerning what he dubs the “disruptive digital archive”.

The paper metaphor is nearing end of life

Sheridan suggests “the deep-rooted nature of paper-based thinking and its influence on our thinking” needs to change and move on. “The archival catalogue is a 19th century thing, and we’ve taken it as far as we can in the 20th century”.

I love a catalogue, but I still agree; and I would extend this to electronic records management. And here I repeat an idea stated some time ago by Andrew Wilson, currently working on the E-ARK project. We (as a community) applied a paper metaphor when we built file plans for EDRM systems, and this approach didn’t work out too well. That approach requires a narrow insistence on single locations for digital objects, locations exactly matching against the retention needs of each object. Not only is this hard work for everyone who has to do “electronic filing”, it proved not to work in practice. It’s one-dimensional, and it stems from the grand error of the paper metaphor.

I would still argue there’d be a place in digital preservation for sorting and curation, “keeping like with like” in directories, though I wouldn’t insist on micro-managing it; and, as archivists and records managers we need to make more use of two things computers can do for us.

One of them is linked aliases; allowing the possibility for digital content sitting permanently in one place on the server, mostly likely in an order that has nothing to do with “original order”, while aliased links, or a METS catalogue, do the work of presenting a view of the content based on a logical sequence or hierarchy, one that the archivist, librarian, and user are happy with. In METS for instance, this is done with the <FLocat> element.

The second one is making use of embedded metadata in Office documents and emails. Though it’s not always possible to get these properties assigned consistently and well, doing so would allow us to view / retrieve / sort materials in a more three-dimensional manner, which the single directory view doesn’t allow us to do.

I dream of a future where both approaches will apply in ways that allow us these “faceted views” of our content, whether that’s records or digital archives.

Get over the need for tidiness

“We are too keen to retrofit information into some form of order,” said Sheridan. “In fact it is quite chaotic.” That resonates with me as much as it would with my other fellow archivists who worked on the National Digital Archive of Datasets, a pioneering preservation service set up by Kevin Ashley and Ruth Vyse for TNA. When we were accessioning and cataloguing a database – yes, we did try and catalogue databases – we had to concede there is really no such thing as an “original order” when it comes to tables in a relational database. We still had to give them ISAD(G) compliant citations, so some form of arrangement and ordering was required, but this is a limitation of ISAD(G), which I still maintain is far from ideal when it comes to describing born-digital content.

I accept Sheridan’s chaos metaphor…one day we will square this circle; we need some new means of understanding and performing arrangement that is suitable for the “truth” of digital content, and that doesn’t require massive amounts of wasteful effort.

Trust

Sheridan’s broad message was that “we need new forms of trust”. I would say that perhaps we need to embrace both new forms and old forms of trust.

In some circles we have tended to define trust in terms of the checksum – exclusively defining trust as a computer science thing. We want checksums, but they only prove that a digital object has not changed; they’re not an absolute demonstration of its trustworthiness. I think Somaya Langley has recently articulated this very issue in the DP0C blog, though I can’t find the reference just now.

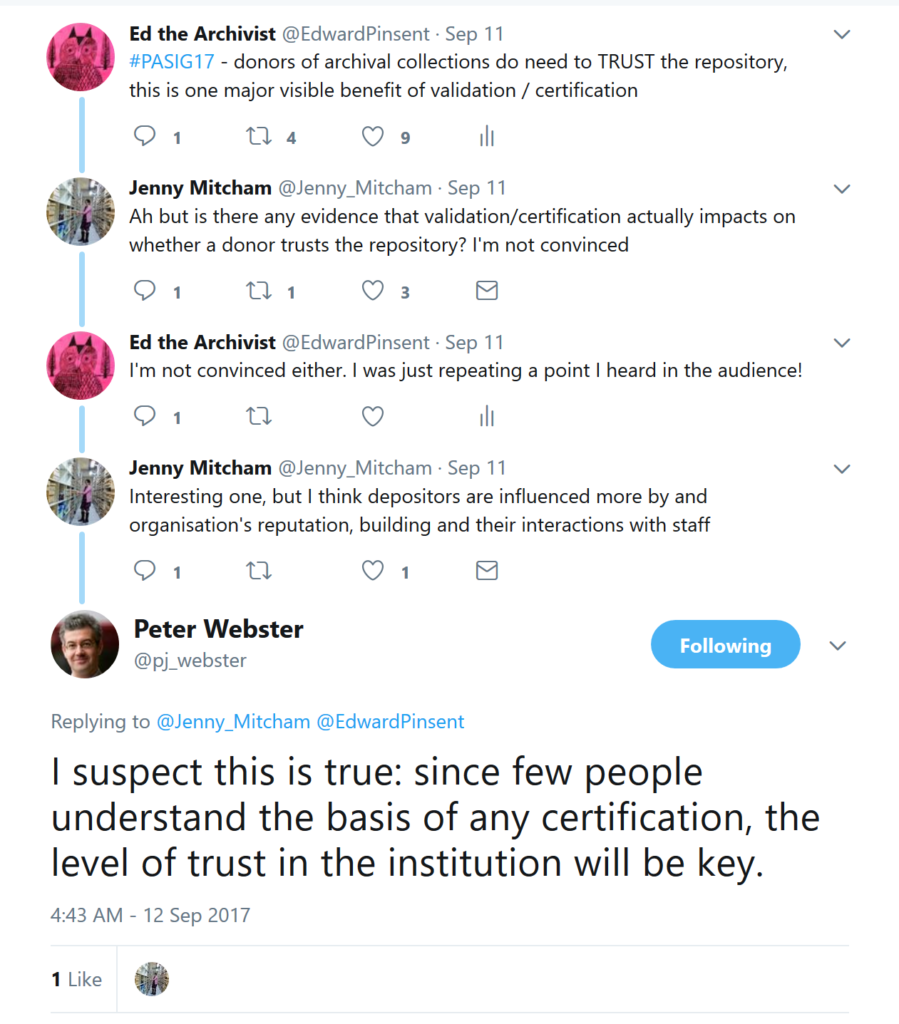

Elsewhere, we have framed the trust discussion in terms of the Trusted Digital Repository, a complex and sometimes contentious narrative. One outcome has been that to demonstrate trust, an expensive overhead in terms of certification tick-boxing is required. It’s not always clear how this exercise demonstrates trust to users…see the Twitter snippet below.

Me, I’m a big fan of audit trails – and not just PREMIS, which only audits what happens in the repository. I think every step from creation to disposal should be logged in some way. I often bleat about rescuing audit trails from EDRM systems and CMS systems. And I’d love to see a return to that most despised of paper forms, the Transfer List, expressed in digital form. And I don’t just mean a manifest, though I like them too.

Lastly, there’s supporting documentation. We were very strong on that in the NDAD service too, a provision for which I am certain we have Ruth Vyse to thank. We didn’t just ingest a dataset, but also lots of surrounding reports, manuals, screenshots, data dictionaries, code bases…anything that explained more about the dataset, its owners, its creation, and its use. Naturally our scrutiny also included a survey of the IT environment that was needed to support the database in its original location.

All of this documentation, I believe, goes a long way to engendering trust, because it demonstrates the authenticity of any given digital resource. A single digital object can’t be expected to demonstrate this truth on its own account; it needs the surrounding contextual information, and multiple instances of such documentation give a kind of “triangulation” on the history. This is why the archival skill of understanding, assessing and preserving the holistic context of the resource continues to be important for digital preservation.

Conclusion

Sheridan’s call for “disruption” need not be heard as an alarmist cry, but there is a much-needed wake-up call to the archival profession in his words. It is an understatement to say that the digital environment is evolving very quickly, and we need to respond to the situation with equal alacrity.