Every so often I am privileged to spend a day in the company of fellow archivists and records managers to discuss fascinating topics that matter to our professional field. This happened recently at the University of Westminster Archives. Elaine Penn and Anna McNally organised a very good workshop on the subjects of appraisal and selection, especially in the context of born-digital records and archives. Do we need to rethink our ideas? We think we understand what they mean when applied to paper records and archives, but do we need to change or adapt when faced with their digital cousins?

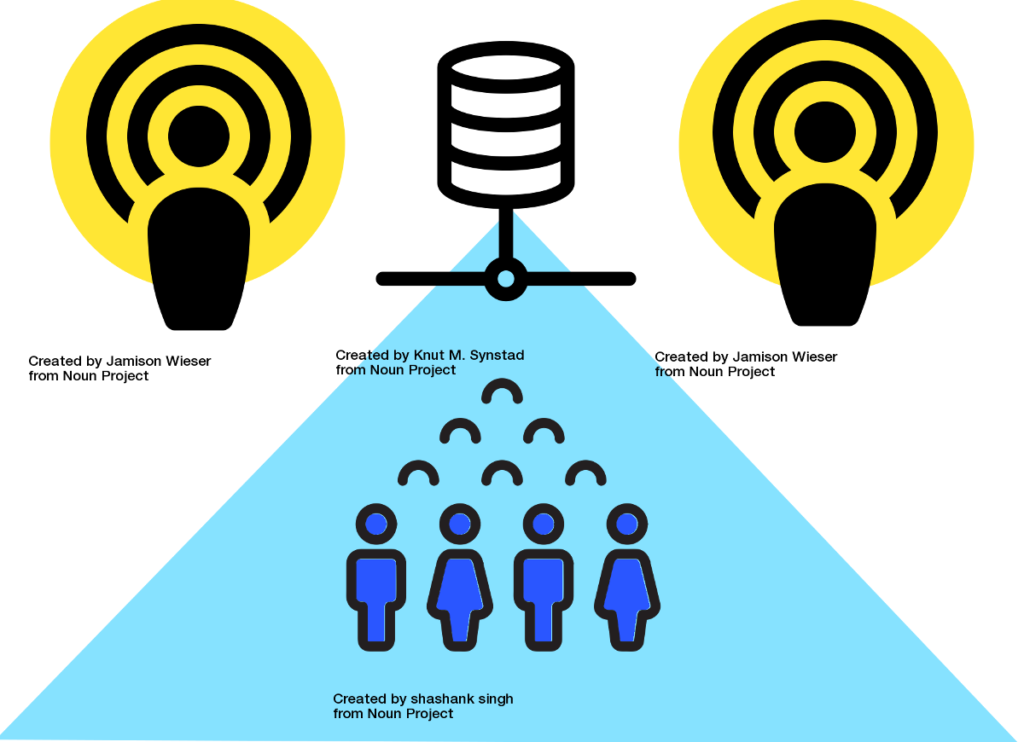

For my part I talked for 25 mins on a subject I’ve been reflecting on for years, i.e. early interventions, early transfer, and anything to bridge the “disconnect” that I currently perceive between three of the important environments, i.e. the live network, the EDRMS or record system, and digital preservation storage and systems. I’m still trying to get closer to some answers. One idea, which I worked up for this talk, was the notion of a semi-current digital storage service. I’m just at the wish-list stage, and my ideas have lots of troubling gaps. I’d love to hear more from people who are building something like this. A colleague who attended tells me that University of Glasgow may have built something that overlaps with my “vision” (though a more accurate description in my case might be “wishful thinking”).

When listening to James Lappin’s excellent talk on email preservation, I noted he invoked the names of two historical figures in our field – Jenkinson and Schellenberg. I would claim that they achieved models of understanding that continue to shape our thinking about archives and records management to this day. Later I wondered out loud what is it that has made the concepts of Provenance and Original Order so effective; they have longevity, to the extent they still work now, and they bring clarity to our work whether or not you’re a sceptic of these old-school notions (and I know a lot of us are). They have achieved the status of “design classics”.

I wonder if that effectiveness is not really about archival care, nor the lifecycle of the record, nor the creation of fonds and record series, but about organisational functions. Maybe Jenkinson and Schellenberg understood something about how organisations work; and maybe it was a profound truth. Maybe we like it because it gives us insights into how and why organisations create records in the first place, and how those records turn into archives. If I am right, it may account for why archivists and records managers are so adept at understanding the complexities of institutions, organisations and departments in ways which even skilled business managers cannot. The solid grounding in these archival principles has led to intuitive skills that can simplify complex, broken, and wayward organisations. And see this earlier post, esp. #2-3, for more in this vein.

What I would like is for us to update models like this for the digital world. I want an archival / records theory that incorporates something about the wider “truth” of how computers do what they do, how they have impacted on the way we all work as organisations, and changed the ways in which records are generated. My suspicion is that it can’t be that hard to see this truth; I sense there is a simple underlying pattern to file storage, networks and applications, which could be grasped if we only see it clearly, from the holistic vantage point where it all makes sense. Further, I think it’s not really a technical thing at all. While it would probably be useful for archivists to pick up some basic rudiments of computer science along with their studies, I think what I am calling for is some sort of new model, like those of Provenance and Original Order, but something that is able to account for the digital realm in a meaningful way. It has to be simple, it has to be clear, and it has to stand the test of time (at least, for as long as computers are around!).

I say this because I sometimes doubt that we, in this loose affiliation of experts called the “digital preservation community”, have yet to reach consensus on what we think digital preservation actually is. Oh, I know we have our models, our standards, systems, and tools; but we keep on having similar debates over what we think the target of preservation is, what we think we’re doing, why, how, and what it will mean in the future. I wonder if we still lack an underpinning model of organisational truth, one that will help us make sense of all the complexity introduced by information technology. We didn’t have these profound doubts before; and whether we like them or not, we all agree on what Jenkinson and Schellenberg achieved, and we understand it. The rock music writer Lester Bangs once wrote “I can guarantee you one thing: we will never again agree on anything as we agreed on Elvis”, noting the diversity of musical culture since the early days of rock and roll. Will we ever reach accord with the meaning of digital preservation?