Chris Loftus at the University of Sheffield has detected a trend among tech giants Google and Microsoft in their cloud storage provision. They would prefer to us make more use of searches to find material, rather than store it in named folders.

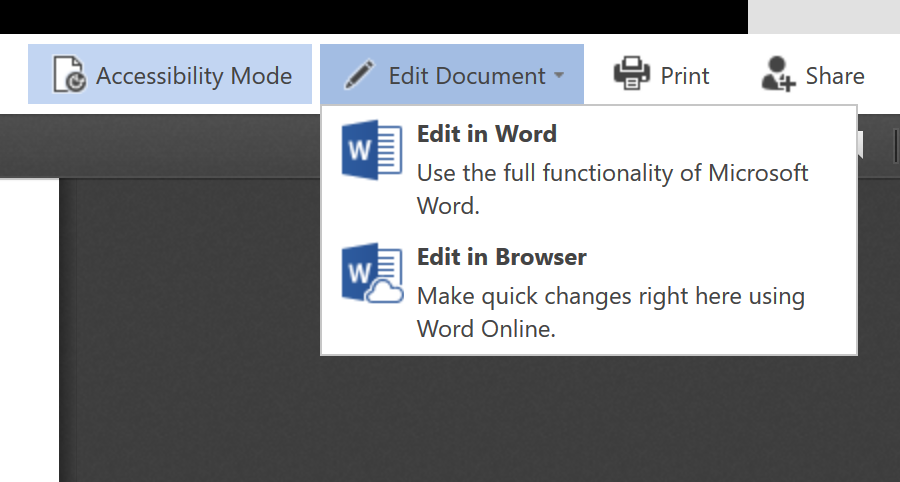

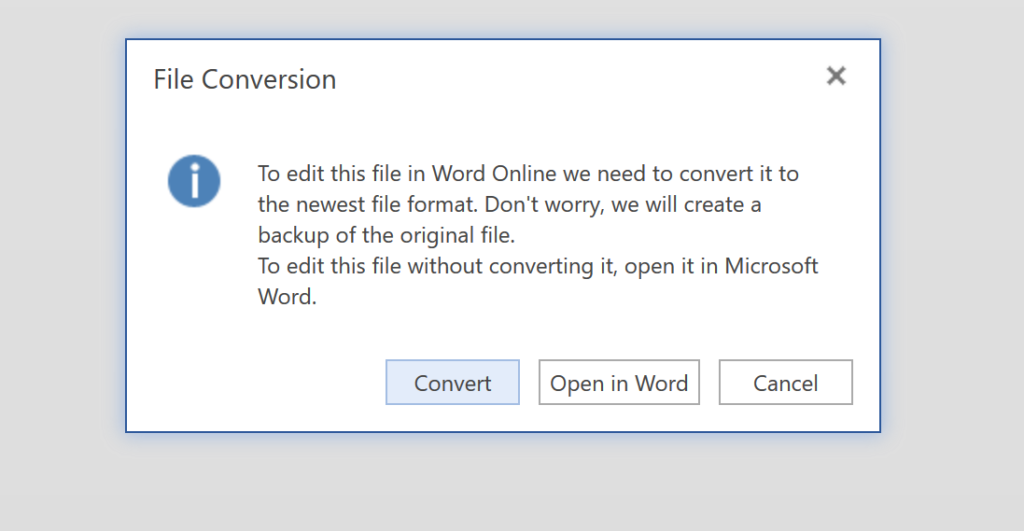

With MS SharePoint at least – which is more than just cloud storage, it’s a whole collaborative environment with built-in software and numerous features – my sense is that Microsoft would be happier if we moved away from using folders. One reason for this might be because these cloud-based web-accessed environments would struggle if the pathway or URL is too long; presumably the more folders you add, the more the string grows, and you make the problem worse. So there’s a practical technical reason right there; we wanted a way to work collaboratively in the cloud, but maybe some web browsers can’t cope.

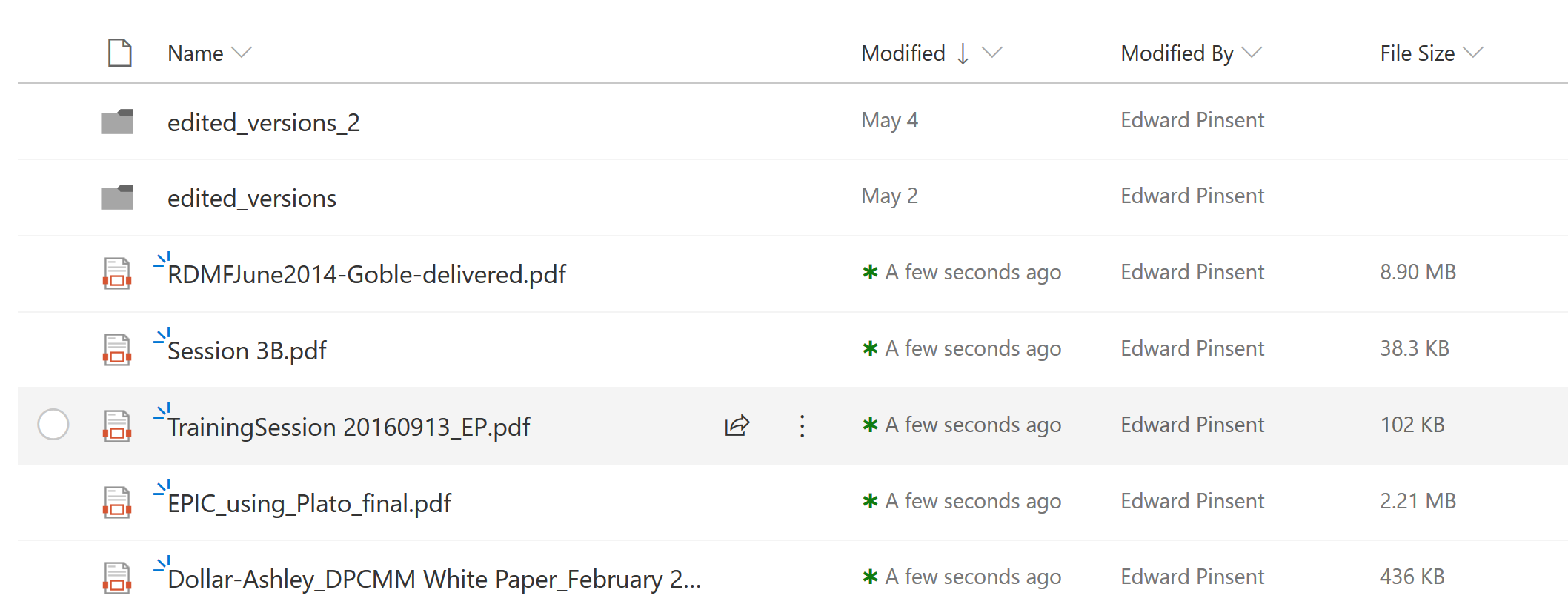

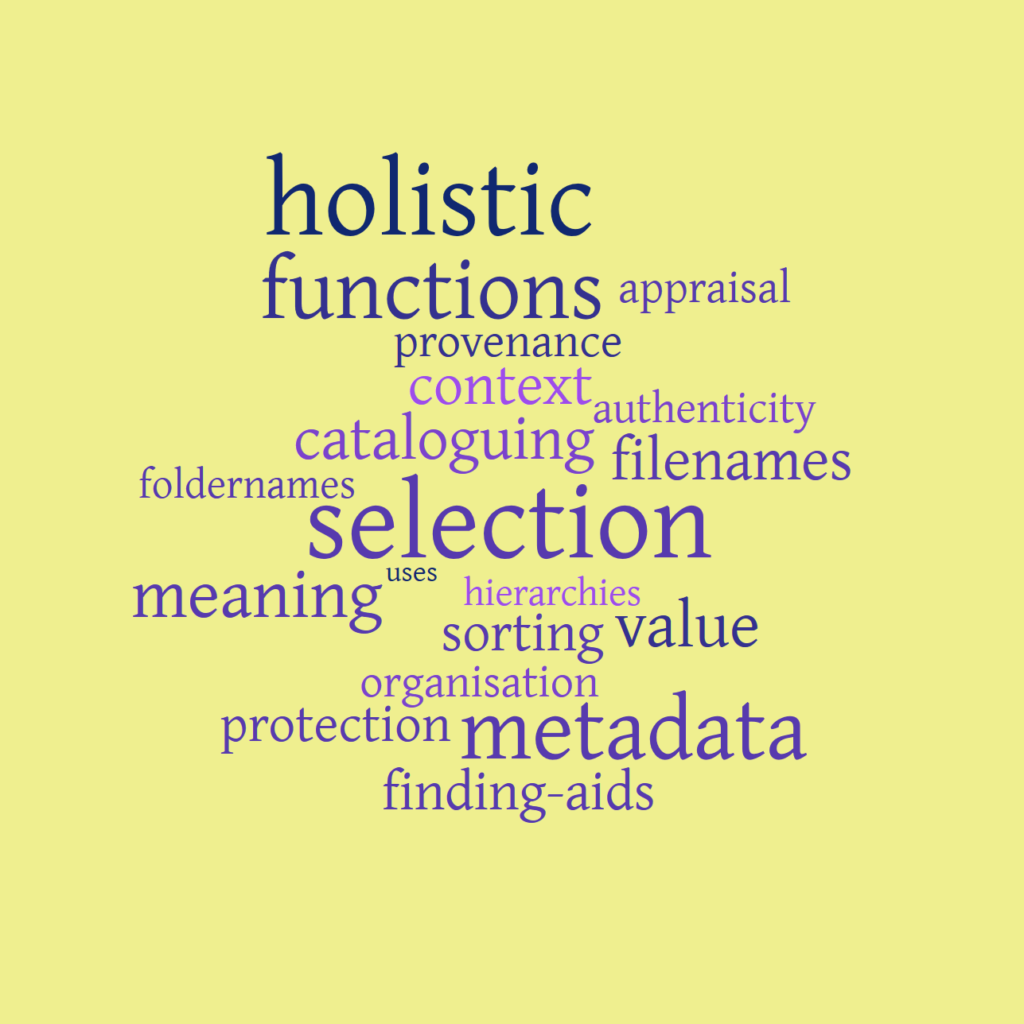

However, I also think SharePoint’s owners are trying to edge us towards taking another view of our content. This is probably based on its use of metadata. SharePoint offers a rich array of tags; one instance that springs to mind is the “Create Column” feature that enables the user to build their own metadata fields for the their content (such as Department Name) and populate it with their own content. This enables the user to create a custom view of thousands of documents, with useful fields arranged in columns. The columns can be searched, filtered, sorted, rearranged.

This could be called a “paradigm shift” by those who like such jargon…it’s a way of moving towards a “faceted view” of individual documents, based on metadata selections, not unlike the faceted views offered by Institutional Repository software (which allow browsing by year, name of author, departments; see this page for instance).

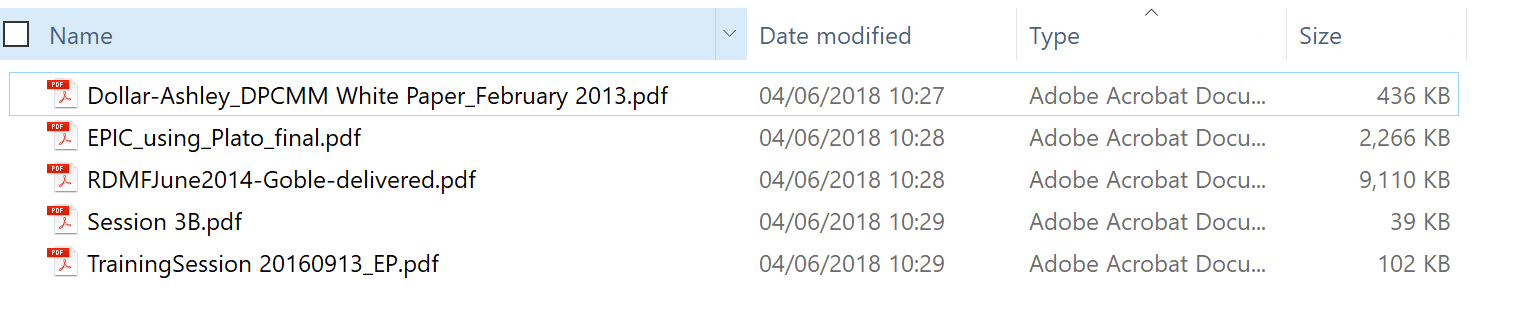

Advocates of this approach would say that this faceted view is arguably more flexible and better than the views of documents afforded by the old hierarchical folder structure in Windows, which tends to flatten out access to a single point of entry, which must be followed by drilling-down into a single route and opening more sub-folders. Anecdotally, I have heard of enthusiasts who actively welcome this future – “we’ll make folders a thing of the past!”

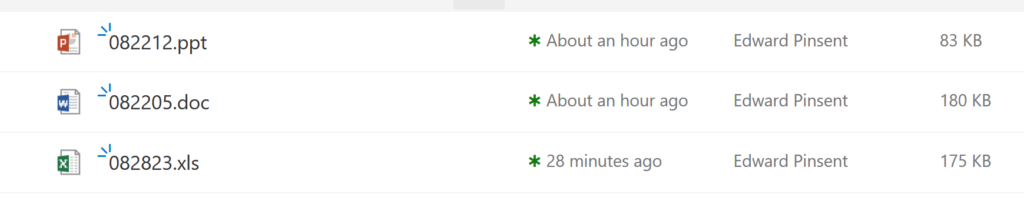

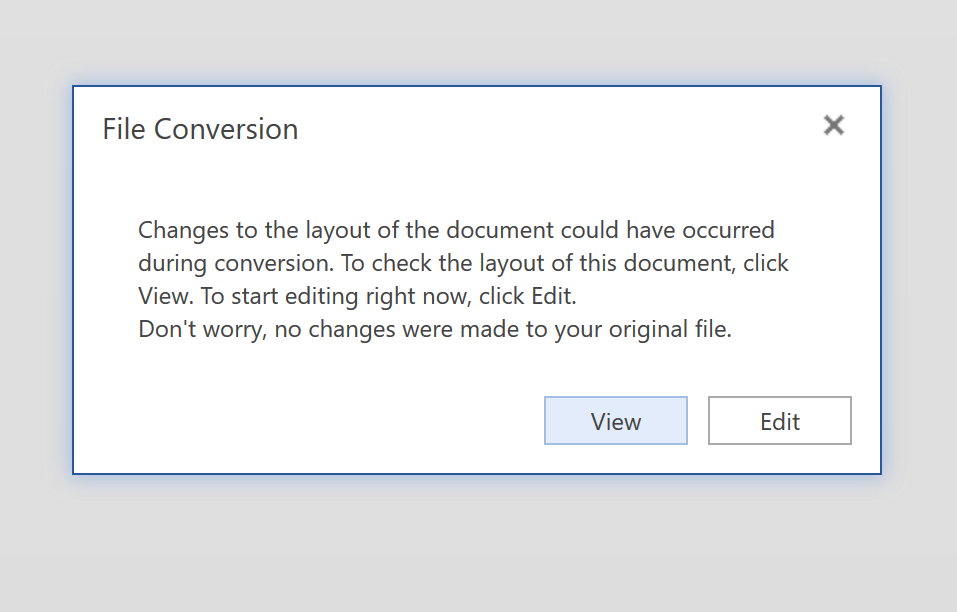

In doing this, perhaps Microsoft are exploiting a feature which has been present in their product for some time now, even before SharePoint. I mean document properties; when one creates a Word file, some of these properties (including dates) are generated. Some of them (Title, Comments) can be added by the user, if so inclined. Some can be auto-populated, for instance a person’s name – if the institution managed to find a way to synch Outlook address book data, or the Identity Management system, with document authoring.

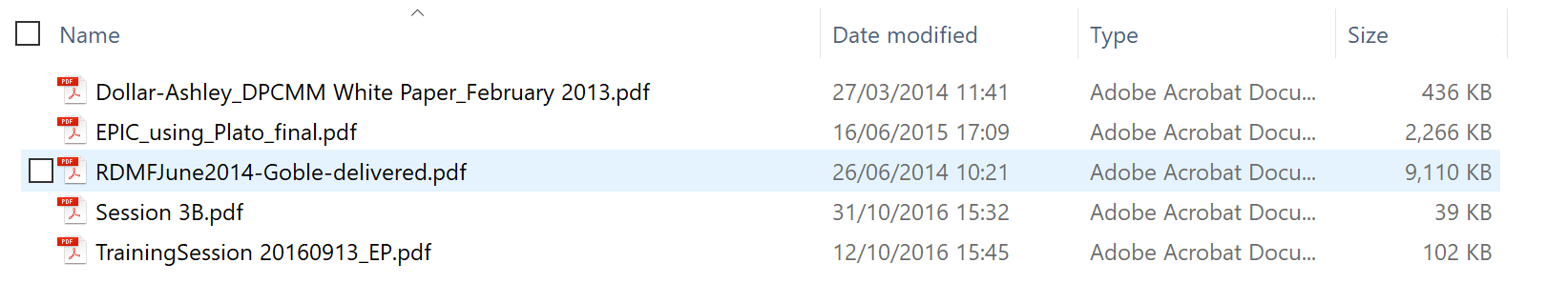

Few users have ever bothered much with creating or using document properties, in my experience. It’s true they aren’t really that “visible”. If you right-click on any given file, you can see some of them. Some of them are also visible if you decide to pick certain “details” from a drop down, which then turn into columns in Windows Explorer. Successive versions of Explorer have gradually tweaked that feature. In one sense, SharePoint have found a way to expose these fields, leverage the properties even more dynamically. Did I mention SharePoint is like a gigantic database?

I might want to add that success in SharePoint metadata depends on an organisation taking the trouble to do it, and configure the system accordingly. If you don’t, SharePoint probably isn’t much of an improvement over the old Windows Explorer way. If you do want to configure it that way, I would say it’s a process that should be managed by a records manager or someone who knows about naming conventions and rules for metadata entry; I seem to be saying it’s not unlike building an old-school (paper) file registry with a controlled vocabulary. How 19th-century is that? But if that path is not followed, might there not be the risk of free-spirited column-adding and naming by individual users, resulting in metadata (and views) that are only of value to themselves.

However, I would probably be in favour of anything that moves us away from the “paper metaphor”. What I mean by this is that storing Word-processed files, spreadsheets and emails in (digital) folders has encouraged us to think we can carry on working the old pre-digital way, and imagine that we are “doing the filing” by putting pieces of paper into named folders. This has led to tremendous errors in electronic records management systems, which likewise perpetuate this paper-based myth, and create the illusion that records can be managed, sentenced and disposed on a folder basis. Any digital change offers us an opportunity to rethink the way we do things, but the paper metaphor gets in the way of that. If nothing else, SharePoint allows us a way of apprehending content that is arguably “truer” to computer science.